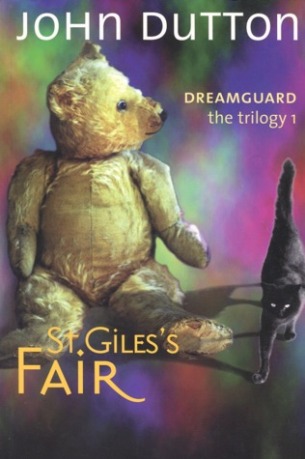

I put ‘trilogy’ in inverted commas because the Dreamguard series was never finished. As best I can tell, the first two books were published either simultaneously or almost simultaneously in early 2000; according to the advert in the back of my editions, the third book was due later the same year, but by the time I was given them to read, maybe 2006, that third book still had not appeared. At present, the series stands are two volumes, out of print and a little hard to get hold of – they’re available via Amazon.co.uk for an excessively high price or failing that from rare-and-out-of-print booksellers. My understanding is that the ‘death’ of the Dreamguard trilogy was down to a severe lack of sales.

It’s strange, because the publishers clearly had a lot of faith in these books – you don’t release two volumes of a series simultaneously unless you feel secure, after all – but I understand exactly why these books were a failure. I understand now and I understood when I was a teenager. It was awkward, because the author, John Dutton (which is a pen-name, but I probably shouldn’t post his real name), was a friend of my grandfather, so I was actually asked to give an opinion to be passed on to him when I was finished. That’s not an opportunity one gets very often and to be honest I think I wasted it.

When I describe Dreamguard as a ‘failure’, I mean it primarily in the commercial sense. As for their quality… they are definitely not bad books. I’m just not sure they’re good books either. These are books which defy classification. Are they for adults? Well, not really – best I can tell, they were marketed as YA and the basic plot is that of a children’s book. Are they for children, then? No – they’re too full of in-depth philosophy to appeal to children (I say that from my own experience – at fifteen I was too young for these books first time around). Is it a trilogy? Not exactly – even aside from the lack of third volume, they’re number consecutively, with the first book being pages 1-300 and the second being pages 200-500. So are they one book intended to be published in three volumes? Regrettably no. The plots of the two published volumes are too distinct. Are they fantasy? Science-fiction? Philosophy? Magical realism? Mythology? It’s probably best to class them as ‘speculative fiction’ and move on but even that doesn’t feel quite right.

Hopefully I have so far managed to convey that these books are strange, and also that I have some pretty strong opinions on them. I actually started this blog partly to have somewhere to post a Dreamguard review. These books deserve a review.

So, to begin, an attempt to summarise the surreal, cerebral and nightmarish journey that is Dreamguard.

Our two heroes, John and Charles, live in Oxford with their highly educated, intellectual parents (I don’t remember if it’s directly stated but I think at least one is connected to the university). They also live with Bear and Tiger, two animal sleeping-bags (no, really) that are their most beloved toys – so beloved that the bond they share is almost spiritual – and with their other stuffed animals, including Seal and Hippo. All four animals later prove very important.

The story opens at a dinner party held by John and Charles’ parents. One guest, Dr Homely-Sage, demonstrates a disturbing hypnotic party-trick on Emer, the boys’ mother. Later the same night, they witness Homely-Sage ensnaring their mother in a spider’s web made of words and spiriting her away in his car. Naturally, they are not believed, and it is assumed by all the adults in their lives that their story is the result of the trauma of abruptly losing their mother.

Over the next few months, John and Charles grow increasingly withdrawn, bringing them onto the radar of Megan, a witch who traps children in her magical television set and feeds on their emotions. John and Charles, being both highly creative and intelligent and highly vulnerable, seem like ideal candidates, so Megan sends her cat, Murgatroyd, to seduce the boys with his charm and his magic and lead them into her trap.

Murgatroyd, however, finds himself befriending John and Charles for real, and comes clean, revealing the whole plan and turning his magic against Megan to protect them. It turns out that Murgatroyd was a demon in a previous life and living out his ‘ninth life’ as a witch’s cat was a punishment for his soft-heartedness. It also turns out that he knows the true identity of Homely-Sage: he is Grayach, the Word-Spider, who lives to destroy beauty and creativity.

In order to protect the boys, Murgatroyd uses his magic to ‘upgrade’ Bear into an Official Dreamguard to keep John safe in his dreams, and sure enough that night Megan launches an attack in the dream world. However, Bear is powerful enough to not only protect John from harm but to break Megan’s power so thoroughly that it’s over a year before she can make another move.

This time, Megan targets Murgatroyd, who is now firmly a member of the family. After being threatened with unimaginable tortures, he reluctantly helps her devise a plan to capture John and Charles at the upcoming St Giles’s Fair. Murgatroyd finds his loyalties so divided that at the fair he uses his magic both to help Megan and to help John and Charles escape. After a chase in the Hall of Mirrors, John, Charles and Murgatroyd are each split in two: Murgatroyd into a good cat and an evil cat and John and Charles in child and adult selves. The child John and Charles are captured by Megan and the evil Murgatroyd; the adult John and Charles escape with the good Murgatroyd onto a time travel ride which Charles, through his own latent magic, transforms into a real time machine.

After an excursion to the time of the dinosaurs and two trips to the future, John, Charles and Murgatroyd decide they must rescue the child John and Charles. They use their new time machine to force their way into Megan’s magical television, only to find that the captured John and Charles have been seduced by the apparent utopia within and are reluctant to leave; not only that, but once Megan notices what has happened, she switches off the television. Only Charles is strong enough to remain conscious and active while the set is switched off, and he enters into a battle of wills with Megan, aided by Hippo, oldest and wisest of his animal companions. Megan, the evil Murgatroyd and the television set are all destroyed, releasing all the children within and fusing John and Charles back into their whole selves. Adventure over, they return home.

In the second volume, Tiger’s Island, the boys meet Egger, a stuffed rabbit who was once their father’s dreamguard and who is now the Administrator of Dreams, ruler of all Dreamguards everywhere.

Shortly thereafter, whilst in the dreamworld together with Bear and Seal (also known as Ickles), John and Charles save a mermaid from some sharks. It turns out the mermaid is actually a girl called Susan, who was just dreaming that she was a mermaid; she tells them that she was investigating a sunken ship when she was attacked. They accompany her back to the ship, only for it to suddenly restore itself. The friendly captain explains that he and his crew are temporarily brought back to life whenever they have visitors; he serves the five of them lunch, then offers each of them a gift.

Susan is given a handkerchief that can heal any injury or illness (even, it later transpires, bring a person back from the dead); John, a keen musician, is given a harp than can warp reality; Charles is given a model horse that can transform into a real horse on his command and which will be eternally loyal; Bear is given a bubble blower (the bizarreness of this is pointed out in the text) which can create almost perfect copies of its bearer, and which he uses to create a Dream Patrol to keep everyone in the Dreamworld safe. Only Seal has the sense to turn down his gift; as the ship returns to the water, John recognises the captain as Grayach.

Unfortunately, it’s too late; the hold of the gifts is too strong. In the real world, John, Charles and Susan sleep solidly for three days, unable to leave the Dreamworld, while Murgatroyd struggles to wake them with his magic. When they finally wake, they explain that they began involved in peaceful, almost utopian, country called Hereza, which was under attack by warlike outsiders. John and Charles, after filling Murgatroyd in, insist that they must return to Hereza as their business their is not yet over.

Deeply concerned, Murgatroyd travels into the Dreamworld himself, to Tiger’s Island. Charles’s Tiger, now a dreamguard himself, controls ever aspect of the island, where he runs a nightclub together with Hippo and a bear named Joey; Seal has also come to the island. Together, they realise that John, Charls and Susan are at risk of being trapped in the Dreamworld forever and so never able to wake up. It’s decided that Hippo and Seal must confront Grayach and find a way to break his hold on the children.

Hippo and Seal journey down to the Land Below Dreams, where Hippo challenges Grayach to a chess match for the fate of the children. If Hippo loses, he will be imprisoned in one of Grayach’s soul-cages. Unfortunately, Hippo doesn’t realise that Grayach is able to read his mind until it’s almost too late: he’s only able to play to a draw, effectively a loss. Thinking fast and desperate for a distraction, Seal demands that Grayach put him in a soul-cage instead. It turns out that according to Grayach’s own rules, he cannot place someone in a soul-cage voluntarily without giving them something in return; Seal takes the opportunity to demand the means to release John, Charles, Bear and Susan, then goes calmly to his fate. Grayach gives Hippo a flask containing the water of ‘hard reality’.

Back in the Dreamworld, Murgatroyd is able, with some difficulty, to convince John, Charles and Susan to drink the water of reality and destroy their gifts, but Bear is another matter. Splitting himself into an army has weakened him so badly that he was at the point of death before being summoned back to Tiger’s Island; even once he has drunk the water and destroyed his gift, he cannot be the bear he once was. Once recovered, he must instead take his place as Administrator of Dreams and Egger’s replacement.

John goes to mourn over the loss of two friends in one day, only for Seal to suddenly return, having been released from his soul-cage. Seal and Hippo request that John and Charles get each of them a wife (i.e. buy another toy seal and hippo) and the book ends with their double wedding.

* * *

And that’s Dreamguard. As for the third book, The Word Spider, I’ve been able to infer that it was to have John, Charles and Susan journey deep into Grayach’s lair, ‘the city of fog and machinery’, and that Susan, who is supposed to be good at solving puzzles, would be the one to ultimately solve the ‘riddle of the word-spider’, presumably freeing Emer. It also would have involved ‘the gift of Itilgi’, characters called Keml, Ngraa and Paari, and something called ‘the hungry images’ which sounds most intriguing.

Except that doesn’t sum up Dreamguard at all. Those summaries, detailed as they may appear, cover maybe half the material here. These books are absolutely stuffed with padding. There’s Herodotean tangents, the obligatory dream sequences, characters ‘filling in’ other characters in great detail on what they’ve been doing since they last met, and on no less than five occasions in Tiger’s Island a character sits down and tells a completely unrelated story to the other characters. Dreamguard is bursting at the seams with padding.

Not to say that’s necessarily a bad thing; it’s beautifully written padding and all of it is presumably at least thematically relevant – I’m not a modern literature person; give me something written in the years B.C. and I’ll be right at home, but I wouldn’t know how to go about puzzling out the purpose behind some some of the material in Dreamguard. It makes both books read like a series of loosely connected vignettes, which is exactly what a dream is like, and Dreamguard is all about dreaming.

However, it’s also very much not a good thing. I gave up on Tiger’s Island on my first attempt, frustrated at its apparent lack of plot and convinced that Mr. Dutton should just have written a short story anthology, since that was clearly what he was actually interested in writing.

That said, as irritating as the ‘sit down and let me tell you a story’ parts are, the ‘filler’ is gorgeous. I’ll try and give you an idea of what sort of thing is in these books: a philosophical penguin. Butterflies made of metal that feed on oil-producing flowers. A future society where everything is obsessively labelled from the people to the trees to the clouds. The tree that grows in the valley of the sun. A giant lying eternally near death after the tree that grew from his chest was uprooted. Almost every character has an extensive backstory that is inevitable related in detail. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Dreamguard is full of vivid, bizarre, beautiful and disturbing images. Up until re-reading them, I couldn’t summarise the plot beyond a vague ‘something about… a witch? With a magic television? And their mother gets kidnapped?’, but hell if I couldn’t describe a lot of scenes in detail, right down to the exact words used. I’m not sure I fully understand the impact reading these books had on my development but I suspect it was significant.

I also feel I should mention that since re-reading them, Dreamguard has cropped up in my own dreams. I think that was inevitable. (It was the part with the lovers whose passion for each other drives them to bite, claw and burn themselves to death. I did say these books were disturbing at times.)

So, then: I like these books. I like them a lot. I didn’t particularly like them at fifteen, but at twenty-one something about them just works. And even if I didn’t like them, I couldn’t help but respect the achievement; these are intricate, vivid books, and it’s obvious from, well, everything about them that they were a labour of love. According to the copyright information John and Charles are based on real people; I’m not sure who they are/were but it’s clear this was a very personal project.

Why, then, am I so unsurprised that they failed? Well, firstly, any book that defies classification as thoroughly as these do is going to be walking a very fine line by default. Then there’s this problem: at fifteen and therefore technically about the right age for YA fiction I was too young to understand the philosophical material but old enough to feel that a book about talking stuffed animals was talking down to me. Anyone young enough to be willing to read a book about living toys is going to be utterly mystified by Dreamguard.

The style is… well. It’s extremely vivid, and it’s certainly not bad, but there’s a big problem with it. I’m going to quote a short passage of dialogue from St. Giles’s Fair and I want anyone to happens to read this to try and guess the respective ages of John and Charles at this point in the narrative (which is long before they get split into child and adult selves). Charles speaks first.

“I could be a grown-up,” he said. “I think. But I have a feeling there’s something more. Some secret I don’t know yet.”

“What sort of secret?”

“Not sure. Their laughter, maybe. Specially when it’s on the other side of a door. Urges working in them when I don’t feel them in me.”

“You’re keen on money,” said John. “And that’s a grown-up thing. True, you’re too young for a love affair.”

“Who’d want one of those! The’re too many round this house as it is. No. Nothing like that.”

“You tell me, then.”

…

“I have the suspicion,” (Charles) said, “that they want the world to make sense.”

“Doesn’t it?”

“Give me one good reason why it should.”

Ready? John is eleven. Charles is nine. Nine. Very intelligent for nine, true. Frequently described as old beyond his years, yes. But still nine. I have yet to meet a nine-year-old who talks like Charles does here. This gets very disconcerting later on; when they’re split into child and adult, there’s no perceptible difference until adult John and Charles encounter child John and Charles… and child John and Charles act nothing like John and Charles did pre-split. Thankfully this gets less aggravating by the second book, as their ages start to catch up with the way they talk, but still.

Pretty much every character talks like that. The result is that the human characters – John, Charles and Susan – are next to indistinguishable from each other in their blandness. The ‘unreal’ animal characters are the ones that really carry the books. I’m not sure if that was intentional or not.

The dialogue issue brings me to by far my biggest problem with Dreamguard. These are some of the most pretentious fantasy books I have ever read. At one point there’s a footnote that directs the reader (and this is a YA book, remember) to look up the tune of a specific Scottish folk song, then provides a full academic-style reference. The third book was to have an appendix containing, amongst other things, fuller details of Grayach and Hippo’s chess match. There’s a whole chapter about the nature of humour. There’s original poetry in Latin embedded into the text (and while I’m not a Latinist, it strikes me as pretty decent poetry). There’s eastern philosophy. There’s pseudo-communist political theory. Every other chapter is an allegory for something or another.

These are books that take themselves very, very seriously, and taking yourself too seriously almost always backfires. I like these books; I think they’re good books. But they’re not good enough to carry that much weight. There’s just too much here; you end up with the intellectual equivalent of sensory overload.

On top of that – I mentioned that John and Charles’s parents are intellectuals. John and Charles are both highly intelligent. Of the animal characters, Tiger and Hippo are both geniuses of almost supernatural skill. The resulting intellectual elitism is… uncomfortable. At one point Murgatroyd tells John and Charles that once released from Megan’s television they’ll be ‘only fit for some office job‘, and both are horrified at the prospect. And yes, being stripped of their creative potential is nasty, but… what’s wrong with office jobs? Not everyone can be a creative genius, after all. I’m not sure ‘intellectual elitism’ is even the right term for this, but whatever it is I don’t like it.

Ultimately, I think the problem with Dreamguard is that it’s too complicated and pretentious to be appreciated by it’s apparent intended audience of children and young adults, but also not really good enough to be appreciated by an adult audience. Plenty of YA books have won nigh-universal acclaim despite confounding younger readers; I just finished re-reading The Owl Service by Alan Garner, which also left me in a state of confusion when I first read it, but which is probably one of the most beloved and most heavily analysed works of fantasy of the last fifty years. The Owl Service succeeds because it’s extremely tightly written and above all because it’s subtle and unpretentious in its fusion of Welsh mythology and the relationship between modern England and Wales. Dreamguard is rarely subtle and never unpretentious.

It’s unfortunate, because I do think that Dreamguard could have succeeded with a better editor. At fifteen I felt that it should have been edited into a fairly straightforward adventure story; now, with a better understanding of the stranger material, I think it could perhaps have been something similar to Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, which also blurs the line between children’s and adult fiction and fuses fantasy with intense philosophy with much greater success. Above all, I think it should have taken itself less seriously. I concur fully with my fifteen-year-old self: no book with talking sleeping bags as central characters has any right to be this pretentious.